Fieldcraft Friday: Who’s Poo Is This?

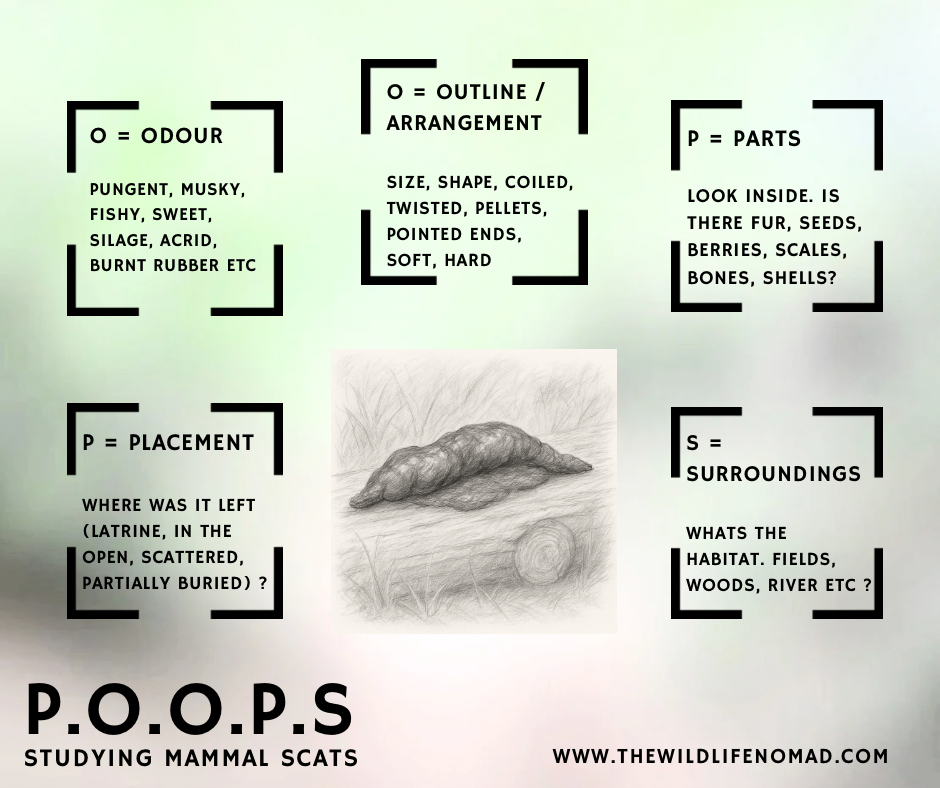

A Fieldcraft Guide to Reading Mammal Scats Using the POOPS Method

We all do it. So does every other animal. The difference is that while we flush and forget, wild mammals leave behind one of the richest sources of field evidence we can find. Call it scat, dung, spraint, droppings, or pellets, to the field naturalist, it’s a signature, a message, a record of who’s been there and what they were doing. Learn to interpret it, and you’ll start to read your landscape like a storybook. This week’s Fieldcraft Friday looks squarely at the subject that makes most people wrinkle their noses…….and yet holds some of the best wildlife clues you’ll ever find.

Let’s find out how to tell who’s poo is this using my field mnemonic POOPS.

Introducing the POOPS Method

P – Placement

O – Odour

O – Outline

P – Pieces (contents)

S – Surroundings

These five cues help you interpret almost any scat you find in the British countryside. They’re quick to apply, easy to remember, and most importantly. they make you slow down, look, and think before guessing.

Let’s take them one by one.

P – Placement

Where an animal leaves its droppings is rarely random. Placement reveals purpose — and understanding why a scat is there is often the key to who left it.

1. Territorial Marking

Foxes, otters, pine martens, polecats, and stoats (among many others) use droppings to communicate. They place them prominently on paths, rocks, logs, or grassy tussocks, somewhere visible (and smellable) to others. A fox’s twisting scat right in the middle of a track is a deliberate “scent post” announcing they passed this way.

Tip: It’s a generalisation, however, if you see scat placed high or in the open, think predator or territorial mammal.

2. Boundary Markers

Scat can be used to mark boundaries. For example, badgers create neat latrines, shallow pits with multiple scats, often along territory edges. Fresh latrines can mark active boundaries; older ones can show long-term clan territories. A single sett may have dozens of such latrines within a few hundred metres.

3. Feeding & Resting Areas

Herbivores drop pellets where they feed or rest: deer in woodland rides, rabbits on lawns, hares on open fields. The distribution often tells you as much as the scat itself, scattered means moving, clustered means resting.

4. Habitual Routes

Riverside sprainting rocks, woodland path crossings, and hedge runs show repeated use. If you find scat on top of old scat, that’s confirmation of a well-established route.

O – Odour

Scent is a language to mammals — and it’s a diagnostic clue for us. You don’t have to get your nose too close (the breeze will do!). Different species have distinct, even surprisingly pleasant smells once you learn them:

The key is to pair smell with placement: musky smell on path (likely fox) sweet jasmine under bridge (likely otter) etc.

Learning odour is best done cautiously, crouch, waft air towards your nose, don’t inhale directly (certainly not if its fox or mink!)

O – Outline

This second “O” refers to the shape and size of the dropping, its outline against the substrate. It’s often the quickest clue.

Shape and size tell you diet, and diet tells you ecology. If it’s fibrous and uniform, the animal likely eats more plant material than meat or fish. If it’s lumpy, twisted, or full of undigested fragments, you’re looking at a predator or omnivore.

P – Pieces (Contents)

This is where the real detective work begins. Use a twig or glove to gently tease apart the scat and examine what’s inside. You’re not just identifying species, you’re peering into last night’s menu. Here’s a few example (but remember like humans most animals vary their diet according to what’s in the larder when they are hungry!)

Carnivores / Omnivores

Fox: small bones, fur, feathers, beetles, berries in summer.

Stoat/Weasel: pure fur and bones; very tight twist.

Otter: fish bones, scales, and shell fragments from crayfish.

Pine Marten: seeds and berries in summer, fur and feathers in winter.

Badger – worms and insects early in the year; fruit, cereals, and acorns in autumn.

Hedgehog – shiny beetle wing cases, worm fragments, slugs.

Herbivores

Deer – compacted grass and leaves; uniform green-brown.

Rabbits & Hares – fibrous plant material, sometimes with visible stems.

By noting the proportions of hair, seed, and bone, you can even gauge seasonal behaviour. A fox eating berries in August versus a fox eating voles in December tells you exactly how it’s using its territory…..and from a photographers perspective where you will have the most lucky watching or recording hunting or feeding behaviour.

S – Surroundings

Finally, take a step back and look at context, the landscape that holds the sign.

Ask: What habitat am I in? What other clues are nearby? A scat alone tells part of the story, but paired with surroundings it becomes conclusive.

Woodland

Badger latrines at path junctions.

Fox and deer sign on tracks.

Squirrel feeding remains (cone cores) nearby.

Grassland & Hedgerow

Rabbit and hare pellets.

Fox scat on boundary stones.

Vole latrines hidden in grass runs.

Rivers & Wetlands

Otter spraints on stones or bridge piers.

Mink droppings similar but darker, stronger smelling.

Water vole latrines neatly piled near burrows.

Moorland & Upland

Deer pellets around bedding scrapes.

Stoat scats along drystone walls.

Fox droppings marking ridgelines.

Noting surroundings also means recording freshness and weathering. A bright, moist dropping may be hours old; dry and cracked means days or weeks. This helps you decide whether the animal might still be nearby.

Putting POOPS into Practice

Let’s work through an example:

You’re walking a riverside path at dawn. On a rock you find a 5 cm scat, dark grey-green, packed with fish scales, smelling faintly sweet.

Placement: Prominent rock beside water.

Odour: Sweet, jasmine-like.

Outline: Irregular, jelly-like.

Pieces: Fish scales and bones.

Surroundings: Riverside, low traffic, smooth stones with older scats nearby.

Run through POOPS and the answer is clear: otter spraint, fresh, possibly from the previous night’s foraging (depending on the weather). Now you know this stretch of river is actively used which is a valuable insight for photography or monitoring.

Common Scats by Species (POOPS at a Glance)

Ethical Fieldcraft with Scats

Ethics always come first. The goal is understanding, not interference.

Look, don’t handle if protected species could be involved, such as otter, water vole, pine marten (in fact wherever possible I try not to disturb the sample, it was left here for a reason and should stay in situ if possible).

Never disturb setts or holts.

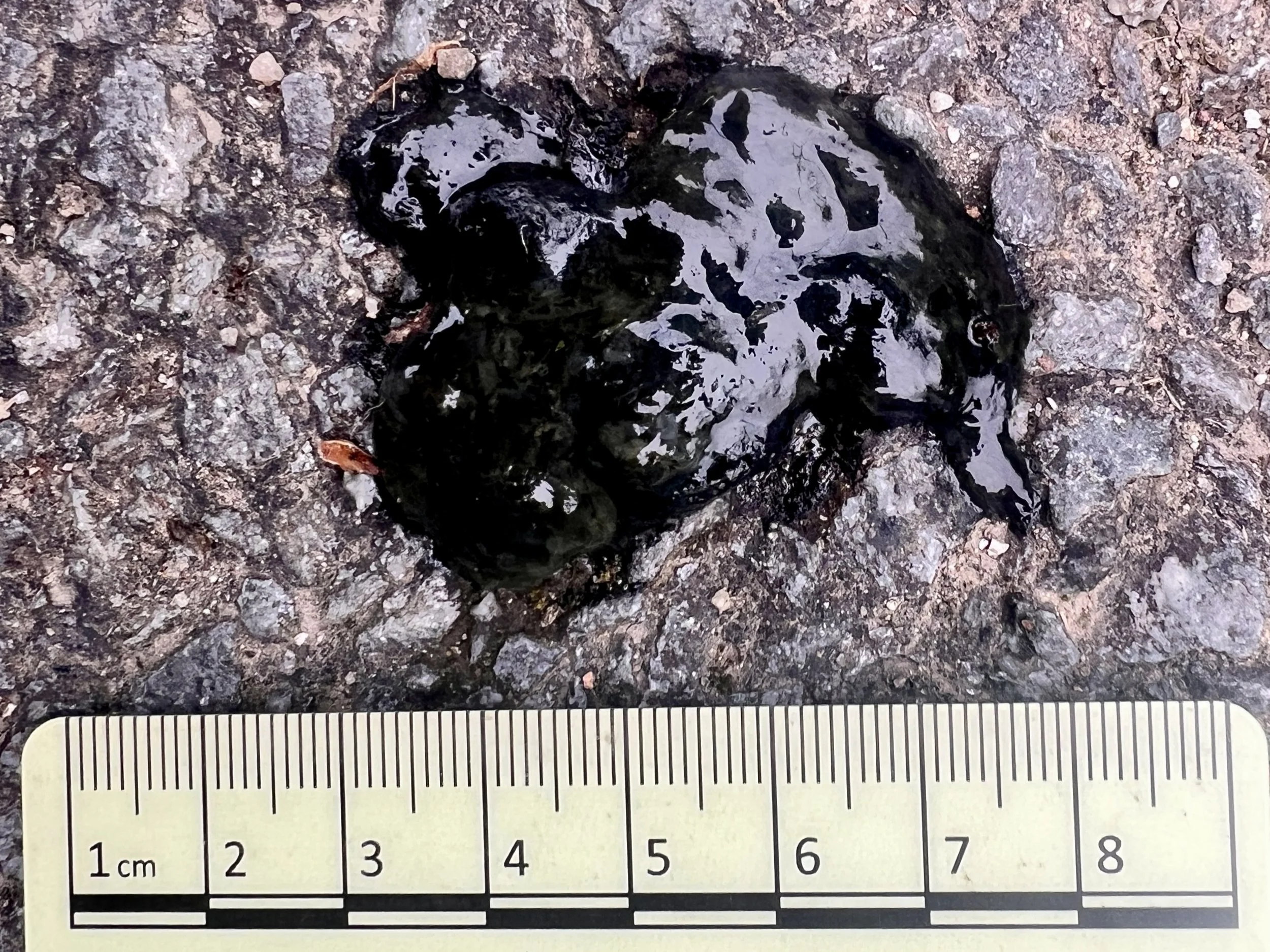

Photograph before you touch. Include a scale card or coin.

Wash hands after any inspection.

Report notable finds (e.g. otter or pine marten scats in new areas) to local Mammal Groups (they’ll thank you).

For photographers, scat images can be surprisingly powerful storytelling tools.

A shallow depth of field and soft side light can make textures visible without sensationalising. Pair your shot with a wide habitat image for educational context.

Seasonal Storytelling Through Scats

Each season paints a different picture. A few examples:

Spring: Earthworms dominate badger scats; foxes show beetles and small mammals.

Summer: Fruit and berry seeds appear everywhere; marten and fox droppings turn purple.

Autumn: Grain, apples, and acorns fill omnivore diets.

Winter: More fur, bone, and scavenged remains, survival fare.

Reading these shifts gives you a window into the natural calendar. A silent chronicle of diet, abundance, and adaptation.

Tools for the POOPS Tracker

Notebook or voice recorder – jot habitat, location, weather.

Scale card or ruler – measure accurately.

Gloves / stick – for gentle inspection.

Hand lens or macro lens – to study contents.

Map or GPS app – to mark recurring sites.

Patience – the most important tool of all.

If you’re running trail cameras, POOPS can help you pick the best spots. Look for Placement (active runs), Odour (freshness), and Surroundings (cover + approach routes). An otter spraint site or fox path marked by droppings almost guarantees repeat traffic. For some species checking out each others smelly messages might be the only interaction they have with each other.

Avoiding the Beginner’s Blunders

Jumping to conclusions – use the full POOPS method before naming.

Ignoring context – habitat is half the evidence.

Touching with bare hands – always use a stick or gloves.

Neglecting to document – photos and notes build long-term insight.

POOPS disciplines you to pause,to observe fully, rather than chase instant answers.

From Curiosity to Connection

It’s tempting to laugh at the idea of studying animal droppings, but once you’ve used POOPS for a few weeks, you’ll see how transformative it is. You begin to sense invisible networks: fox paths threading through hedgerows, otter territories defined by regular sprainting points, badger clan lines etched into the landscape.

You stop being a visitor and start becoming a reader, and with time and practice will be someone fluent in the written language of the wild.

Next time you find yourself crouched over an interesting pile of something on the path, remember: you’re not strange, you’re observant. Every scat, pellet, or latrine is a message left by another life sharing this place.

Apply POOPS, take your notes, and walk on a little wiser. Because true fieldcraft isn’t about finding animals, it’s about understanding their traces.

Other Blog Articles Of Interest

Learn about badger diet across the seasons

Know Deer behaviour and signs (including droppings) to get better shots

More about Pine Marten foraging ecology, and caching behaviour (and how their scat help us ID their prey preferences).

—————————————————-

FAQ: Identifying Mammal Scats in the UK

How can you tell the difference between fox and dog droppings in the UK?

Fox droppings are typically twisted at one end, often left on prominent features such as paths, rocks, or grassy tussocks, and contain fur, feathers, or small bones. They’re deliberate scent marks.

Dog droppings are usually blunter and softer, left at random, and contain processed food remnants rather than wild prey.

Use POOPS: Placement (on track), Outline (tapered), and Pieces (fur or feathers) point clearly to fox.

What does a badger latrine look like and where is it found?

Badgers create shallow pits known as latrines, with several droppings often deposited together. The scats vary in consistency depending on diet — firm and grainy when eating cereals, softer when they’ve eaten worms or fruit.

These latrines are found along woodland paths or territory edges, marking clan boundaries. The key identifiers are Placement (in a pit) and Surroundings (near sett or trackway).

How can I tell how fresh a scat is?

Fresh droppings are moist, glossy, and strongly scented; older ones are dry, dull, and cracked. Rain, sunlight, and insects all accelerate weathering, so learn to judge by both texture and odour. For example, a fresh otter spraint still carries a sweet, musky scent, while an old one turns grey and flaky.

In POOPS terms, note Odour and Surroundings to estimate age.

What should I do (or not do) when I find mammal droppings?

Observe, don’t disturb. Many species, such as otters, water voles, and badgers, have legal protection, meaning it’s an offence to interfere with their setts or latrines. Avoid touching fresh droppings with bare hands, photograph before moving anything, and never collect samples unless licensed or conducting approved survey work.

Ethical fieldcraft means respecting wildlife even when it’s not present.

How can I tell herbivore droppings from carnivore droppings?

Herbivores (deer, rabbits, hares) produce round or oval pellets, uniform in texture and filled with fibrous plant matter. Carnivores (fox, badger, stoat, weasel) leave tubular, often twisted scats with fur, bones, and insect remains visible.

The POOPS cues here are Outline (shape) and Pieces (contents): smooth and fibrous (plant matter) equals grazer; twisted and coarse (hair & bone) equals predator.