European Badger (Meles meles): Diet, Foraging Ecology and Feeding Behaviour

1. Abstract

The European badger (Meles meles) is a widespread and ecologically significant member of the Mustelidae family. Although commonly regarded as an omnivore, its diet is dominated by earthworms, supplemented by seasonal fruits, insects, crops, and small vertebrates. Unlike other mustelids such as the pine marten, the badger does not cache food but relies on fat accumulation in autumn to survive periods of reduced activity during winter. This article synthesises current knowledge of badger feeding ecology, highlighting seasonal variation in diet composition, calorific value of resources, foraging strategies, and the species’ role in shaping ecosystems.

2. Methods

Most studies of badger diet employ scat analysis, stomach content examination, or direct observation at setts and foraging grounds (Kruuk 1978; Neal & Cheeseman 1996). Quantitative assessments have been conducted in Britain and across Europe, with earthworm biomass measured through soil sampling (Kruuk & Parish 1981), and fruit and nut consumption recorded by phenological surveys of available resources (Kowalczyk et al. 2003). Seasonal variation is typically expressed as percentage occurrence in scats or as biomass contributions. The data presented here are drawn primarily from long-term studies in southern England, Wales, and continental Europe.

3. Seasonal Diet Composition

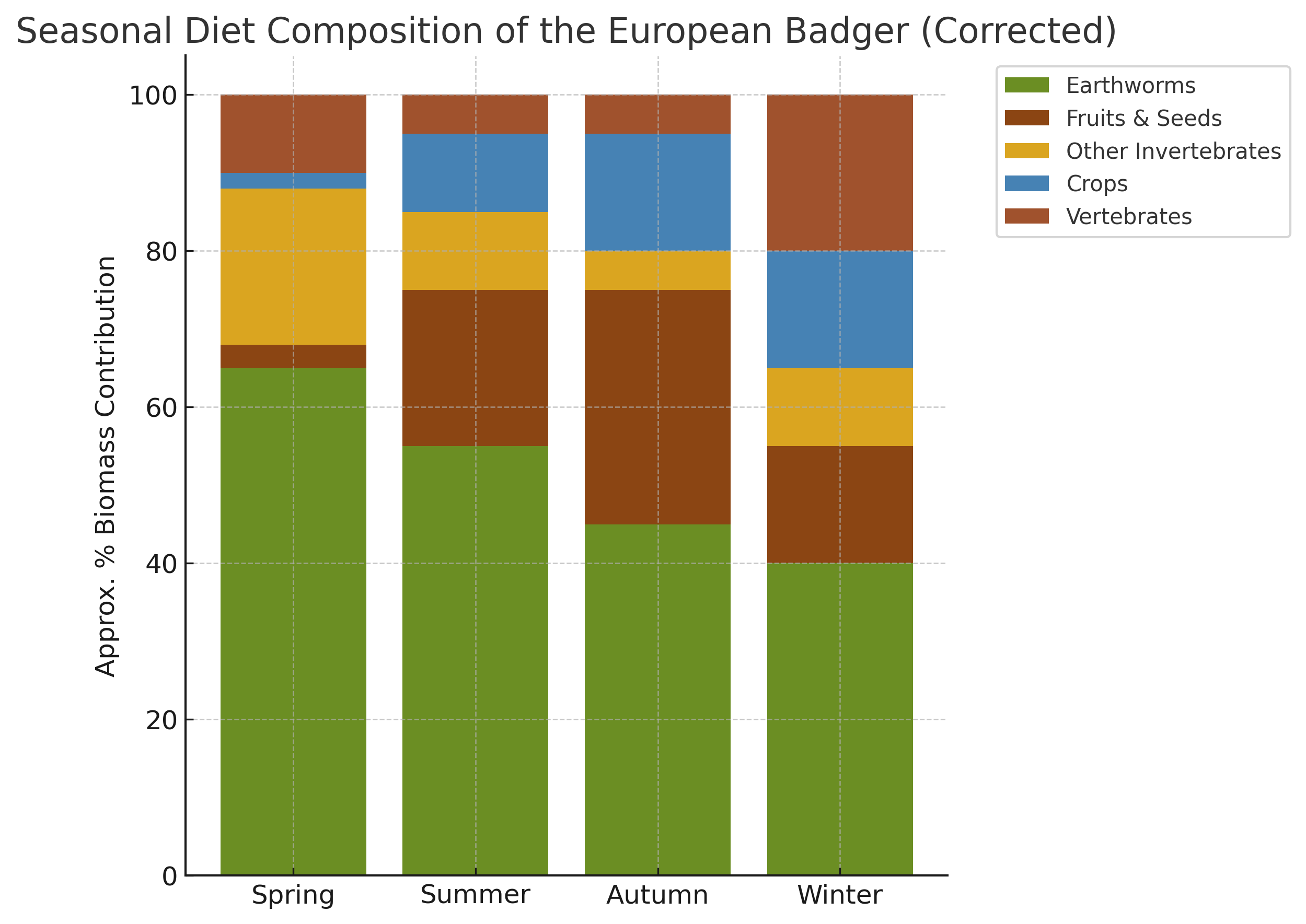

The diet of the European badger is dominated by a small number of key food items, supplemented opportunistically (Kruuk 1978; Macdonald & Newman 2002). Corrected figures ensure each seasonal profile sums to ~100%.

Spring (March–May):

Earthworms: 65%

Other invertebrates (beetle larvae, insects): 20%

Vertebrates (young rabbits, voles, eggs): 10%

Fruits & seeds: 3%

Crops: 2%

Summer (June–August):

Earthworms: 55%

Fruits (berries, orchard fruit): 20%

Crops (maize, wheat): 10%

Other invertebrates: 10%

Vertebrates: 5%

Autumn (September–November):

Earthworms: 45%

Fruits & nuts (blackberries, apples, hazel, beech mast, acorns): 30%

Crops (maize, apples, pears): 15%

Other invertebrates: 5%

Vertebrates: 5%

Winter (December–February):

Earthworms: 40%

Vertebrates & carrion: 20%

Fruits & seeds (windfalls, berries): 15%

Other invertebrates: 10%

Crops: 15%

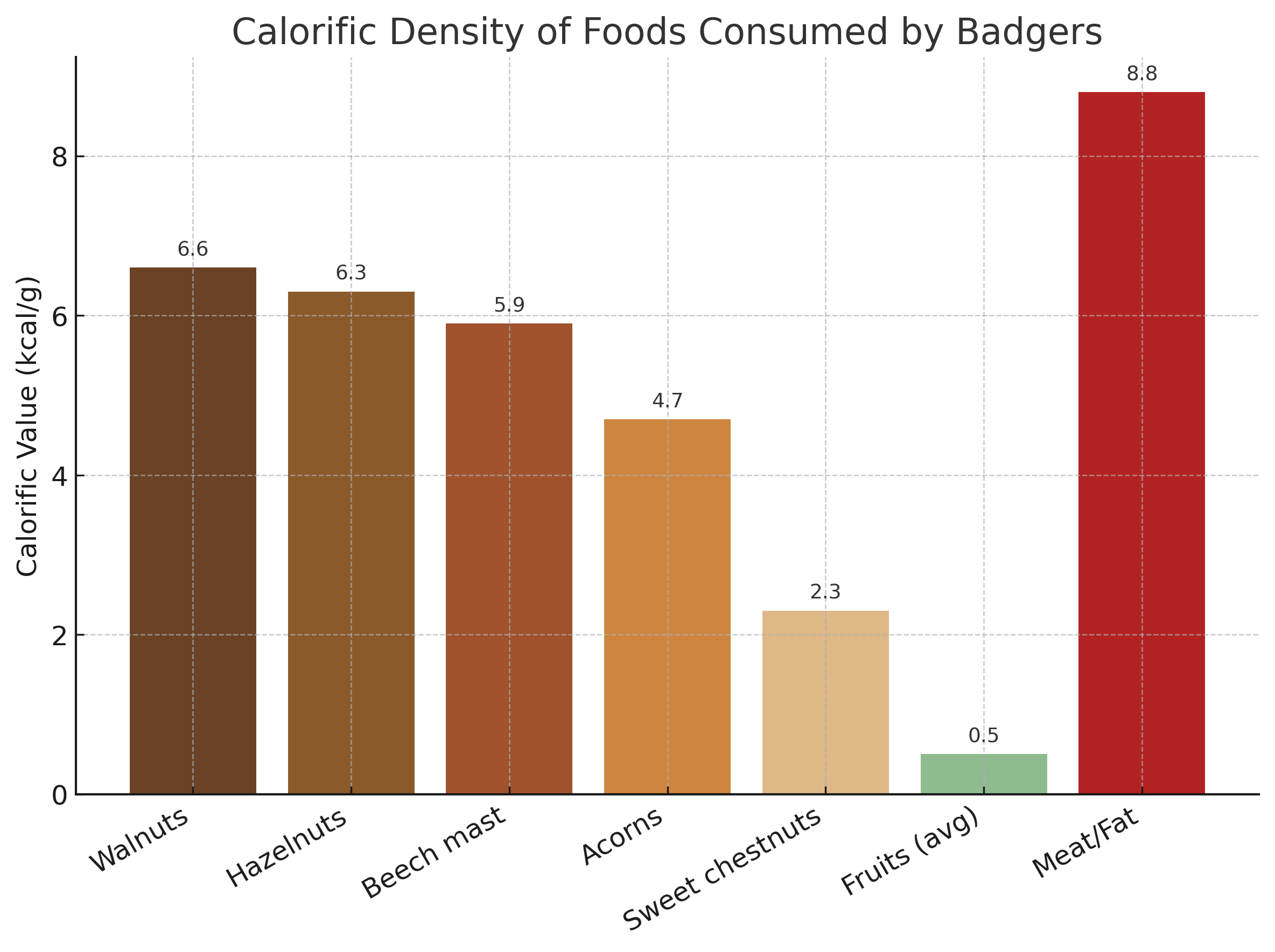

4. Calorific Value of Foods Consumed

The energetic return of different foods helps explain why badgers focus heavily on nuts in autumn.

Walnuts (Juglans regia): ~6.5–6.7 kcal/g

Hazelnuts (Corylus avellana): ~6.3 kcal/g

Beech mast (Fagus sylvatica): ~5.8–6.0 kcal/g

Acorns (Quercus robur/Q. petraea): ~4.5–5.0 kcal/g (variable; tannins reduce digestibility)

Sweet chestnuts (Castanea sativa): ~2.0–2.5 kcal/g

Fruits (apples, blackberries, plums): ~0.4–0.6 kcal/g

Compared gram-for-gram, walnuts are the richest plant-based food regularly eaten by badgers in Britain, slightly higher than hazelnuts or beech mast, and vastly richer than fruit. One walnut kernel can equal the energy of 10–12 blackberries.

Foods Higher in Calories Than Walnuts

The only regularly encountered foods more energy-dense are animal fat and meat (8–9 kcal/g), obtained opportunistically through carrion or predation (Doncaster et al. 1990). These are unpredictable compared with the seasonal reliability of nuts and fruit.

This explains why badgers gorge on walnuts, hazelnuts, beech mast, and acorns during September–October: they are the most profitable and predictable autumn fuel to build fat reserves before winter semi-torpor.

5. Foraging Ecology

Badgers exhibit a highly specialised foraging method for earthworms, using olfactory cues to detect prey below the surface (Kruuk & Parish 1981). They forage most effectively on moist soils in pastures and woodland glades. Foraging routes are habitual, with well-worn paths connecting setts to feeding sites, often marked by latrines and scent posts (Roper 2010). Group size and social structure correlate with habitat productivity: richer, worm-abundant pastures support larger social groups, while marginal uplands host smaller, more dispersed clans (Macdonald & Newman 2002).

6. Feeding Behaviour and Strategies

Unlike pine martens, badgers do not cache or hoard food. Instead, they accumulate fat reserves, sometimes increasing body mass by 30–40% in late autumn (Roper 2010). This strategy allows them to survive prolonged winter inactivity. Feeding is typically solitary, though multiple members of a clan may forage in the same meadow without conflict. Badgers are primarily nocturnal, with peak foraging activity 1–3 hours after sunset (Neal & Cheeseman 1996).

7. Opportunism and Predation

Although their diet is dominated by earthworms and fruit, badgers remain opportunistic feeders. They will predate rabbit kittens, hedgehogs, rodents, and ground-nesting birds where the opportunity arises (Doncaster et al. 1990). In some regions, badgers are known to excavate wasp nests to consume larvae. However, vertebrate prey rarely exceeds 10% of annual intake and is highly variable by site.

8. Ecological Role

Badgers play an important role in soil turnover and nutrient cycling through their foraging activity (Roper 2010). Their digging exposes subsoil layers, aerates the ground, and redistributes organic matter. Latrines may act as seed dispersal points, particularly for fruiting shrubs consumed in autumn (Kowalczyk et al. 2003). By regulating earthworm populations locally, badgers may indirectly influence soil structure and fertility (Kruuk & Parish 1981).

9. Implications for Observation and Photography

For wildlife photographers, an understanding of diet and foraging ecology provides seasonal opportunities:

Spring: Badgers active on damp pasture after rain, best photographed at ground level with telephoto lenses.

Summer: Foraging around orchards and berry patches, offering chances for wide-angle or low-light work.

Autumn: Feeding in orchards or beneath oak and hazel trees, often predictable and prolonged. Ideal for behavioural sequences.

Winter: Reduced opportunities, but snow tracking near setts may reveal brief foraging excursions.

Ethical considerations are paramount. Avoid baiting with artificial food, as this alters natural behaviour. Instead, use fieldcraft to position yourself downwind of trails, and employ red-filtered lights or passive infrared cameras where night visibility is necessary.

10. Conclusion

The European badger’s diet reveals a balance between specialisation and opportunism. At its core lies an extraordinary dependence on earthworms, yet the species adapts flexibly to seasonal fruits, nuts, crops, and occasional vertebrate prey. The calorific analysis explains why high-energy foods such as walnuts, hazelnuts and beech mast are so heavily targeted in autumn: they offer the most efficient fuel for winter survival. For naturalists and photographers, learning these seasonal rhythms is not only key to successful encounters but also a reminder of how closely badgers’ fortunes are tied to the productivity and health of their landscapes.

More detail on badger ecology and field sign can be found here

References

Doncaster, C. P., Dickman, C. R. & Macdonald, D. W. (1990). Feeding ecology of the European badger (Meles meles): a review. Mammal Review, 20(2-3), 97–116.

Kowalczyk, R., Bunevich, A. N. & Jędrzejewska, B. (2003). Badger (Meles meles) diet in Białowieża Primeval Forest (Poland) compared with other European populations. Ecography, 26(5), 539–551.

Kruuk, H. (1978). Foraging and spatial organisation of the European badger, Meles meles L. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 4, 75–89.

Kruuk, H. & Parish, T. (1981). Feeding specialisation of the European badger Meles meles in Scotland. Journal of Animal Ecology, 50(3), 773–788.

Macdonald, D. W. & Newman, C. (2002). Population dynamics of badgers (Meles meles) in Oxfordshire, UK: Numbers, density and cohort life histories, and a possible role of climate change in population growth. Journal of Zoology, 256(2), 121–138.

Neal, E. & Cheeseman, C. (1996). Badgers. Poyser Natural History, London.

Roper, T. J. (2010). Badger. Collins New Naturalist Library, London.

—————————————————————————————

Badger FAQ

Are badgers native to the UK?

Yes. The Eurasian badger (Meles meles) is native to Britain and has lived here since the Ice Age. It’s one of our most widespread and recognisable mammals.

Where do badgers live?

Badgers live in underground burrow systems called setts, usually dug into banks, woodland edges, or hedgerows. A large sett may have many entrances and house several generations.

How can you tell if a badger sett is active?

Look for fresh digging, tracks, and well-worn paths leading to the entrances. Bedding (dried grass or bracken) dragged outside is another clear sign of recent activity.

What do badger tracks look like?

Badger prints are broad and hand-like, with five toes and long claw marks. They often appear along woodland paths or muddy gateways.

When are badgers most active?

Badgers are mainly nocturnal. They emerge from their setts at dusk and return before dawn, though cubs may come out earlier on summer evenings.

Are badgers protected in the UK?

Yes. Badgers and their setts are legally protected under the Protection of Badgers Act 1992. It’s illegal to harm them or disturb their setts.

How can you watch badgers ethically?

Pick a sett with signs of activity, sit downwind at dusk, stay quiet, and keep your distance. Use binoculars or a telephoto lens rather than approaching closely.