Recording Nature in the Digital Age: iNaturalist, iRecord, Mammal Mapper & the NBN Atlas

A naturalist’s notebook goes digital

Think back to the first time you scribbled down a wildlife sighting. Maybe it was a hedgehog crossing the garden path, or a roe deer slipping between trees at dusk. If you’re like me, that record probably stayed in a notebook, a half-faded pencil sketch, or a photo buried somewhere on your phone.

The difference now is that those observations don’t have to sit in the dark. With a handful of apps, you can take what you’ve seen and make it part of something much bigger: a national, even global, picture of how wildlife is doing. The question is — which app should you use, and how do they all fit together?

Three names crop up again and again: iNaturalist, iRecord, and Mammal Mapper. They sound similar, but each one is a bit different. And behind them all sits the NBN Atlas — the central storehouse of UK biodiversity data.

iNaturalist — the social butterfly of wildlife recording

If you want something quick, friendly, and a bit fun, iNaturalist is where most people start. You open the app, snap a photo of whatever you’ve seen (a beetle on a gatepost, a buzzard overhead, a plant on a walk) and the app’s AI takes a stab at the ID. Sometimes it nails it, sometimes it’s hilariously wrong, but it gives you a starting point.

Other people in the community then weigh in. Two or three confirmations later, your sighting gets labelled “Research Grade” and is whisked off to global databases. It feels like a blend of Instagram and science: you post, people respond, and suddenly you’re part of something worldwide.

The catch? It isn’t foolproof. A hazy photo of a brown moth will get all sorts of guesses, and the UK’s recording schemes don’t always trust iNaturalist data at face value. Think of it as a brilliant entry point and a great way to learn, but not the last word in recording.

iRecord — the serious, slightly nerdy one

If iNaturalist is the friendly extrovert, iRecord is the diligent note-taker. Built in the UK for UK wildlife, iRecord is where data goes if you want it to count. Records you enter are reviewed by expert verifiers from groups like the Mammal Society or Butterfly Conservation. That hedgehog in your garden? If you log it here, it can directly shape conservation reports.

The trade-off is that iRecord doesn’t hold your hand. There’s no AI to help with IDs, so you need at least a fair idea of what you’re looking at. The interface can feel a bit clunky too. But once you get used to it, you realise why it matters: this is the system conservationists actually use and trust.

If you’re serious about contributing to UK datasets, iRecord is the gold standard.

Mammal Mapper — small, focused, and badly needed

Then there’s Mammal Mapper. This one is like a pocket field notebook built specifically for mammal people. It was created by the Mammal Society because, bluntly, our data on UK mammals is thin. Birds have thousands of records, butterflies have armies of watchers, but mammals? They’re shy, nocturnal, and hard to monitor.

Mammal Mapper lets you walk a route and log live sightings or field signs — badger latrines, stoat tracks in snow, otter spraints. Even roadkill gets recorded, because it all adds up. Unlike the generalist apps, this one is laser-focused: every record goes straight to the Mammal Society, who use it to map distributions and push for stronger protection.

It’s not as flashy, and you need some confidence with tracks and signs, but if mammals are your passion this app is a direct line to helping them.

The NBN Atlas — the UK’s biodiversity library

The NBN Atlas (National Biodiversity Network Atlas) is best thought of as the UK’s biodiversity library. Instead of shelves and books, it holds hundreds of millions of individual records of plants, animals, fungi and habitats. Each “record” is simply a sighting tied to a date and a place.

What’s stored there?

Species sightings: from stoats and hedgehogs to lichens and fungi.

Datasets: uploaded by charities, recording schemes, local record centres, and government bodies.

Interactive maps: which show distributions across the UK.

Metadata: who collected the record, when, and under what licence.

Who can access it?

Everyone!

It’s free and open-access. Ecologists, planners, academics, students, conservationists, or just curious people can all use it. Sensitive species (like raptors or rare orchids) often have their exact location blurred, but the broader patterns remain.

How does it work behind the scenes?

The Atlas is a hub. Records flow in from:

Local Environmental Record Centres

National schemes and societies (Mammal Society, Butterfly Conservation, BTO, etc.)

Apps like iRecord and Mammal Mapper (after verification)

Global databases like GBIF (where iNaturalist data is hosted)

The Atlas doesn’t collect data itself — it just brings everything together into one searchable, public platform.

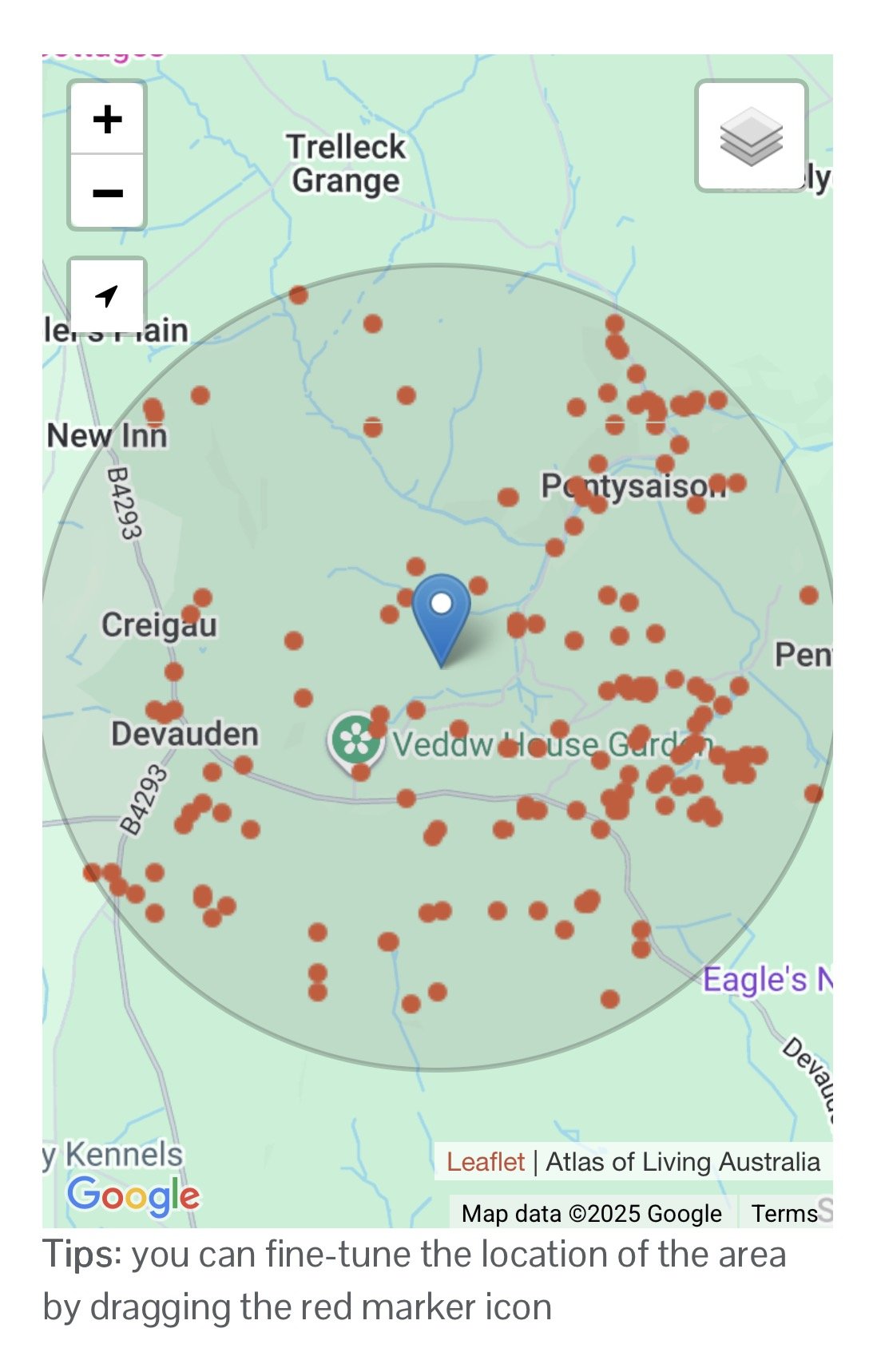

Using the Atlas yourself: example, searching for specific species in your area

Let’s say you’re in the Monmouthshire countryside near Devauden and want to know if a particular species is present. Here’s how you’d use the Atlas:

Go to NBN Atlas.

Search for your required species.

Open the species page and you’ll see a UK distribution map.

Use filters: select Region, then zoom into your location.

The map now shows many red dots near your location, each one an individual record of that species.

Apply the filter “last 5 years” to see recent sightings.

Click a record point: you’ll see the year it was logged, the dataset it came from, and sometimes the recorders name.

Now you know: your species is active in your location and exactly where it has been recorded (woodland, rough ground, river valley etc). That information confirms you’re not just chasing shadows! Pair it with fresh field signs like scat on logs or runs through grass, and you’ve got a solid lead for where to focus your fieldcraft and wildlife photography.

(Please note for rarer species exact location data is not provided, just a more generalised locator on the map).

Why it matters

This is the power of the NBN Atlas: it connects your personal sightings with the bigger picture. One stoat record might not seem much, but added to dozens across your county, or hundreds across the UK, it builds a map of distribution and change. For photographers, it helps narrow where to spend those precious dawn and dusk hours. For conservationists, it’s evidence for protecting habitats. For naturalists, it’s a resource that deepens understanding of your own patch.

A quick cheat sheet

If you’re the sort who likes a side-by-side summary, here’s a simple table to compare the three apps:

As someone who spends a lot of time behind the lens, I’ve found these tools shift how I look at wildlife. A fox slinking through bracken isn’t just a photo — it’s a record. A badger sett isn’t just fieldcraft — it’s data.

By sharing what we see, we add our voices to a bigger story. In an age of rapid change, every record fills a gap. iNaturalist helps us learn, iRecord ensures our data is trusted, Mammal Mapper gives mammals the attention they need, and the NBN Atlas ties it all together.

The takeaway is simple: don’t let your sightings vanish into your notebook or photo archive. Log them, share them, and let them become part of the record. One stoat scat, one hedgehog crossing, one roe deer sighting ……..together they make the map of Britain’s wildlife richer and more useful for all of us.

References & Useful Links

iNaturalist (App Store / Google Play / Web)

iRecord (App Store / Google Play / Web)

Mammal Mapper (App Store / Google Play / Web)

NBN Atlas

NBN Atlas User Guide – how to search, map, and download data

NBN Atlas YouTube tutorials – step-by-step video guides

Mammal Society Resources

Mammal Society survey methods – full guidance on field survey techniques

————————————

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the NBN Atlas and why is it important?

The NBN Atlas (National Biodiversity Network Atlas) is the UK’s central online repository for biodiversity data — species sightings, historical records, datasets, maps, and associated metadata. It provides open access (with some restrictions for sensitive species) so researchers, conservationists, planners, and nature lovers can see what wildlife has been recorded where.

It matters because it aggregates data from many sources: local record centres, national surveys, citizen scientists, and apps like iRecord or Mammal Mapper. By pooling all that, it gives a much more complete picture of species distributions, trends over time, and helps guide conservation decisions.

2. Who can access data on the NBN Atlas, and are there any restrictions?

Everyone can access much of the NBN Atlas data. It’s free to use, and records are searchable and viewable. Some data (especially for rare or vulnerable species) may have restricted location detail (“blurred”, generalised) to protect those species.

Records are licensed under Creative Commons (CC0, CC-BY, or CC-BY-NC) or Open Government License (OGL), meaning many are usable even for commercial or research purposes — depending on the licence.

3. How does wildlife surveying work in the UK? What are common methods?

Wildlife surveying in the UK involves different approaches depending on the target species, habitats, and the question being asked. Some common methods:

Field signs: tracks, droppings, gnawed plants, nests or burrows.

Transect walks & circuits: fixed-routes that are surveyed repeatedly to record presence and changes over time.

Camera traps & trail cameras: capture images of mammals, especially nocturnal or shy species.

Live capture / release for small mammals: using humane traps to capture, identify, count, then release.

Citizen science surveys: e.g. the PTES “Living with Mammals” project.

These methods, repeated over time, help build robust data on what species are present, their numbers, and how distributions change.

4. Which mammals are most under-recorded, and why does that matter?

Many small mammals (field voles, shrews, harvest mice) are under-recorded because they are cryptic, small, nocturnal, and hard to trap or observe. Predators like stoats and weasels are also elusive.

Under-recording matters because if you don’t know a species is present (or declining), it may go unnoticed until declines are large and harder to reverse. Conservation actions depend on good data; policies and habitat protection rely on knowing “where” and “how many” of a species there are.

5. How do records from apps like iNaturalist, iRecord or Mammal Mapper get onto the NBN Atlas?

Here’s how the flow usually works:

iRecord and Mammal Mapper: records are submitted by users, verified by experts, then passed to local record centres or national schemes, which share them with the NBN Atlas.

iNaturalist: data (especially “Research Grade”) goes first to GBIF, and some of that is accessed by UK systems. With iNaturalistUK, integration with the NBN is improving.

Verification & licensing are crucial: only records with proper evidence, metadata, and permissions are shared.

6. How can I find out what mammals are around my area using the NBN Atlas?

Here’s a simple way:

Go to NBN Atlas and search for the species you’re curious about (e.g. “Stoat”).

Use filters to narrow by region (e.g. your county), by date (last 5–10 years), or by dataset.

Zoom into your local map area to see recent clusters of sightings.

Click on a record point to view details (date, dataset, sometimes recorder).

This gives you a clear sense of whether species have been recorded nearby and helps guide your own surveys.

7. What legal protections do mammals in the UK have, and how do surveys tie in?

Many mammals are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and other legislation. These laws protect certain species from deliberate disturbance, killing, or destruction of resting/breeding sites.

Survey data feeds directly into planning and environmental impact assessments. For example, if surveys find bats or badgers on a development site, developers must adapt or mitigate their plans to avoid harming them.

8. How many mammal species are there in the UK?

The UK has around 101 native and non-native mammal species (depending on how you count reintroductions and vagrants). Of these, about half are regularly recorded wild residents. These include common species like foxes, roe deer, and hedgehogs, but also rarer ones such as dormice, pine martens, and the reintroduced beavers.

Non-native species such as grey squirrels, muntjac deer, and American mink also form part of the UK’s mammal community. Understanding which are native and which are introduced is crucial for conservation priorities.

9. What are the major threats to UK mammal species right now?

Key threats include:

Habitat loss & fragmentation — hedgerows removed, fields intensified, woodlands cut.

Road casualties — huge impact on species like badgers, hedgehogs, deer, and otters.

Pollution & pesticides — reducing prey availability or causing toxin build-up.

Climate change — shifting habitats and food availability.

Under-recording — if declines aren’t noticed due to lack of data, species can slip away unnoticed.

10. How reliable are citizen science records, and how are they verified?

Citizen science plays a huge role, but reliability is managed carefully:

Verification: experts review unusual records before acceptance.

Evidence: photos, sound recordings, or clear field signs strengthen validity.

Community review: iNaturalist uses consensus, iRecord uses expert verification, and Mammal Mapper links directly to the Mammal Society.

The combination of citizen effort and expert checking makes the system robust and hugely valuable.