Fieldcraft Friday: Reading Otter Footprints

The Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) is one of Britain’s most elusive mammals. You can walk the same riverbank for years without ever seeing one — but you can be certain they’ve seen you. Luckily, otters leave behind one of the clearest calling cards in the naturalist’s toolkit: their footprints.

This week, I’ll walk you through how to recognise them, from paw morphology to how impressions change across different substrates, using real examples photographed in the field (for more details on Otter watching and photography look here and here).

Why Tracks Matter

Tracks are the language of the landscape. They tell us who passed by, how they moved, and sometimes even what mood they were in. For otters, footprints are especially valuable because they often appear alongside other signs such as spraint, slides, or feeding remains, and together these clues build a picture of territory and behaviour.

If you’re patient enough to slow down and read them, you can uncover the hidden story of an otter long after it has moved on.

Anatomy of an Otter Print

Otters are semi-aquatic predators, and every part of their foot reflects that lifestyle:

Five toes on both front and hind feet, forming a gentle arc. In practice, you’ll often only see four.

Broad heel pad — rounded on the forefoot, longer and more rectangular on the hind.

Short claws that may leave faint marks in firmer substrates.

Webbing between toes, sometimes visible in deep mud or fine sand.

Size: Fore prints are usually 6–7 cm wide; hind prints 7–9 cm long — much bigger than mink.

Plaster cast of an otter footprint in sand. Even though the edges blur, the broad pad and five-toe structure stand out.

Track Impressions in Different Substrates

Otter prints rarely look the same twice. Conditions change everything:

Soft mud or clay: Clear toes and pads, sometimes with webbing.

Sand or silt: Edges soften quickly, leaving ghostly outlines.

Gravel or pebbles: Broken or partial prints — look for repetition across a trail.

Snow: Excellent for showing gait and sometimes playful slides.

Grass or leaf litter: Almost invisible, unless damp or frosty.

Towpaths and banks: Partial prints where otters haul out.

Preserved otter paw — the broad pads and short claws match the shape seen in tracks.

Where to Find Otter Footprints

Otter prints aren’t only by the water’s edge. Keep an eye out in:

Riverbanks & sandbars — especially fords and small beaches.

Canal towpaths & locks — soft mud is perfect for prints.

Bridges & weirs — otters cross here frequently.

Ponds & lakes — muddy margins often hold tracks.

Reedbeds & marshes — channels reveal otter traffic.

Farm tracks & ruts — puddled mud can capture prints.

Snowy fields in winter — sometimes overland journeys leave trails kilometres long.

Otter footprint with a key for scale — typically 6–8 cm wide, much larger than mink or stoat.

A trackway running straight down to water, showing the otter’s purposeful movement.

A partial print in damp sand. Even fragments add evidence when seen in sequence.

Otter vs. Mink

The most common confusion is with American mink. To tell them apart:

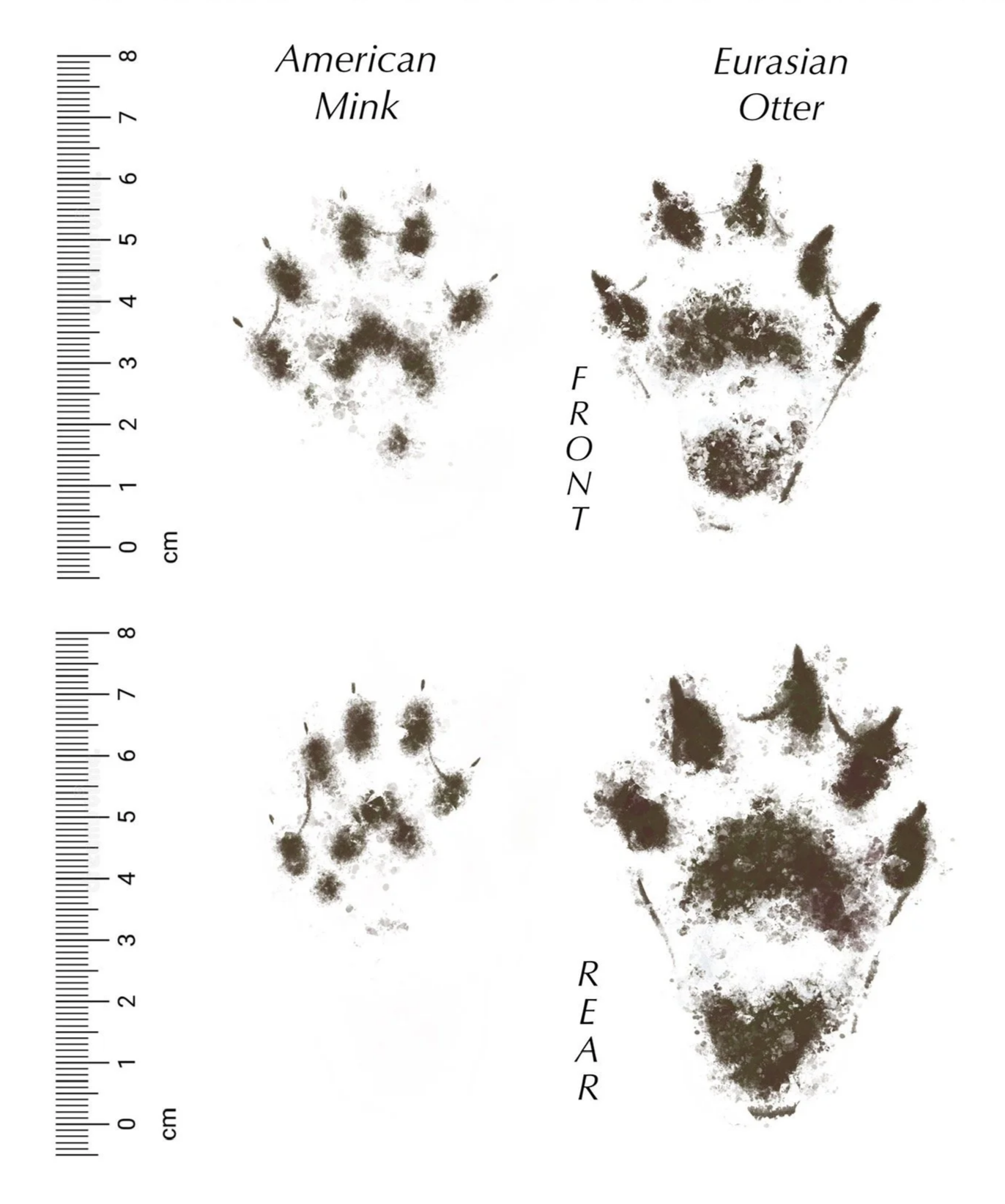

Size: Otter 6–9 cm, Mink 2.5–4 cm.

Setting: Otters rarely stray far from water; mink roam more widely.

Stride: Otters move directly and purposefully; mink often zig-zag.

My field journal illustration showing front (rounder) and hind (longer) otter prints (sometimes with webbing), compared to American mink.

Fieldcraft Tips

Scan slowly — use soft eyes to catch subtle shapes.

Use light — morning or evening light highlights edges.

Photograph with scale — always include a coin, key, or ruler.

Combine signs — tracks with spraint or feeding remains confirm presence.

Closing Thoughts

Otter tracks are not just marks in mud — they’re signatures in a hidden diary. They show where an otter moved, paused, and slid back into the water.

So next time you walk a riverbank, don’t just look across the current. Look down. The otter was there before you, and with patience, you’ll begin to read its story.

In case you missed the links at the start of this blog, more details on otter watching and photography can be found here and here.

——————————

Frequently Asked Questions about the Eurasian Otter

Q1: What is a Eurasian Otter and where is it found?

A: The Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra) is a semi‐aquatic carnivore native to much of Europe and parts of Asia and North Africa. In the UK, it inhabits rivers, lakes, wetlands, canals and even coastal areas where there’s fresh water nearby.

Q2: What do Eurasian Otters look like (size, appearance)?

A: Otters have sleek, dense brown fur with a paler belly, a long tapering tail, short legs, webbed feet, a broad nose, and small ears. Adults typically measure 60-90 cm in body length (excluding tail) and can weigh 6-11 kg on average. Males tend to be larger than females.

Q3: What do Eurasian Otters eat?

A: Their diet is varied but mostly fish. They also eat amphibians, crustaceans, insects, small mammals, and even birds or eggs when opportunity arises. In times when fish stocks are low, they diversify their diet.

Q4: When are otters most active, and what are their behaviour patterns?

A: Eurasian Otters are largely crepuscular or nocturnal (active at dawn, dusk, and night), though in areas of low human disturbance and good cover they may sometimes be seen during daylight hours. They are solitary, territorial animals, using scent (spraint) to mark territories. Breeding can occur year‐round, but most cubs are born between May and August in the UK.

Q5: What is a “holt” and where do otters make their dens?

A: A “holt” is the otter’s den. Otters build or adopt dens in cavities in riverbanks (e.g. among exposed roots), under rocks, in root systems, or between boulders. Sometimes they use abandoned burrows or natural crevices. Holts often have multiple entrances, some above and sometimes under water.

Q6: Are Eurasian Otters endangered or at risk in the UK?

A: They are protected under UK law (e.g. Wildlife & Countryside Act) and are considered a conservation success story in many parts of the UK thanks to improved water quality, pollution regulation, and habitat restoration. However, threats remain: road collisions, habitat destruction, illegal trapping, entanglement in fishing gear, and chemical pollutants. Their status is “Least Concern” in Great Britain overall, but in some devolved nations they are still classed as Vulnerable.

Q7: How long do Eurasian Otters live?

A: In the wild, most live around 5-10years though a few may live longer under favourable conditions. Captive individuals may live somewhat longer.

Q8: How can I increase my chance of spotting an otter in the wild?

A: Some tips include:

Choose quiet times (dawn/dusk) when disturbance is low.

Look near water edges, bridges, weirs, and slip-in points.

Search for indirect signs: spraint, slides, feeding remains.

Use vantage points overlooking water, especially where cover is dense.

Watch for trails along banks, often muddy or sandy.

Coastal areas with freshwater input (rivers/streams) are good.