European Pine Marten (Martes martes) Diet, Foraging Ecology, and Caching Behaviour

A well adapted crepuscular‐nocturnal hunter, the Pine Marten’s activity is flexibly timed to prey activity and thermoregulation.

Abstract

This overview integrates published data on the European pine marten’s seasonal diet composition (both at the category and species levels), foraging movement, energetic intake versus expenditure, and food‐caching behaviours. We quantify monthly biomass intake by prey type, estimate daily caloric returns, summarise daily movement patterns, and characterise caching volumes and composition across seasons, drawing conclusions on the ecological drivers of each strategy.

1. Introduction

As an opportunistic mesocarnivore, the pine marten’s foraging strategy reflects both seasonal prey availability and energetic demands. Food‐caching—long thought to buffer against resource scarcity—has only recently been documented in detail using den boxes and camera traps (Twining et al. 2017). Here, we bring together dietary, movement, energetic, and caching data to present an integrated view of marten ecology in boreal systems.

2. Methods

Diet Composition: Averaged percent biomass by season from scat and gut analyses in Sweden, Poland, Finland (Helldin 2000; Jędrzejewski et al. 1993; Pulliainen & Ollimäki 1996; Zalewski & Jędrzejewska 2002).

Foraging Movement: Daily movement distances (DMD) from telemetry studies (Strickland & Douglas 1987; Gilg et al. 2003).

Energetics: Energy densities (kcal/g fresh mass) from nutritional studies (Muñoz‐Garcia & Williams 2005); FMR estimated as 2–3× BMR of ≈82 kcal/day (Gilg et al. 2003; Martin et al. 2020).

Caching Data: Food caches recorded in artificial den boxes in Scotland and Northern Ireland: prey counts, dates, and composition (Twining et al. 2017)

Fruit is a key food source for Pine Martens at various times of the year. One, named "Pip," was spotted in late May plucking cherries from the highest branches of a tree. Interestingly, a Red Squirrel was in the same tree, less than 10 feet away, sharing the same feast. Neither seemed to care about the other's presence.

3. Seasonal Diet Composition

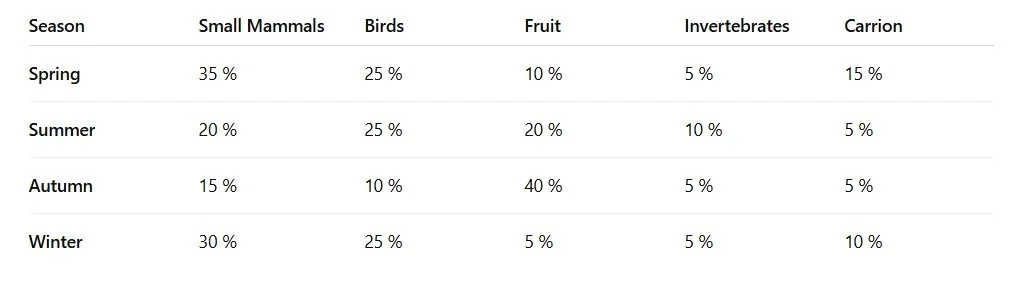

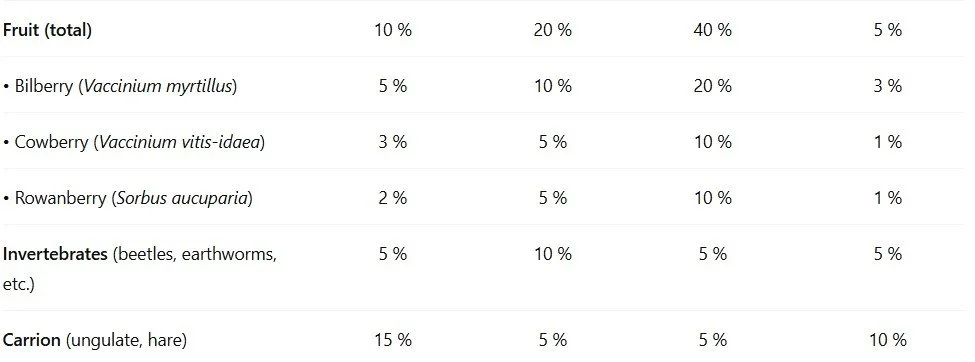

3.1. Category‐Level Biomass (% of Total)

3.2. Species‐Level Biomass by Season

4. Foraging Behaviour and Movement

Activity Pattern: Crepuscular‐nocturnal, flexibly timed to prey activity and thermoregulation.

Daily Movement Distance (DMD):

Spring/Summer: 3–5 km/day on average; peaks up to 12.7 km/day during breeding‐season demands .

Autumn: 2–4 km/day, reflecting clustered fruit resources .

Winter: 0.4–3 km/day, reduced by snow cover and energetic constraints.

5. Energetic Intake vs. Expenditure

5.1. Requirements

BMR: ≈82 kcal/day; FMR: ≈250–500 kcal/day (2–3× BMR) .

5.2. Estimated Caloric Intake

Assuming 200 g daily intake (~20 % body mass):

6. Food‐Caching Behaviour

6.1. Typical Cache Composition & Volumes

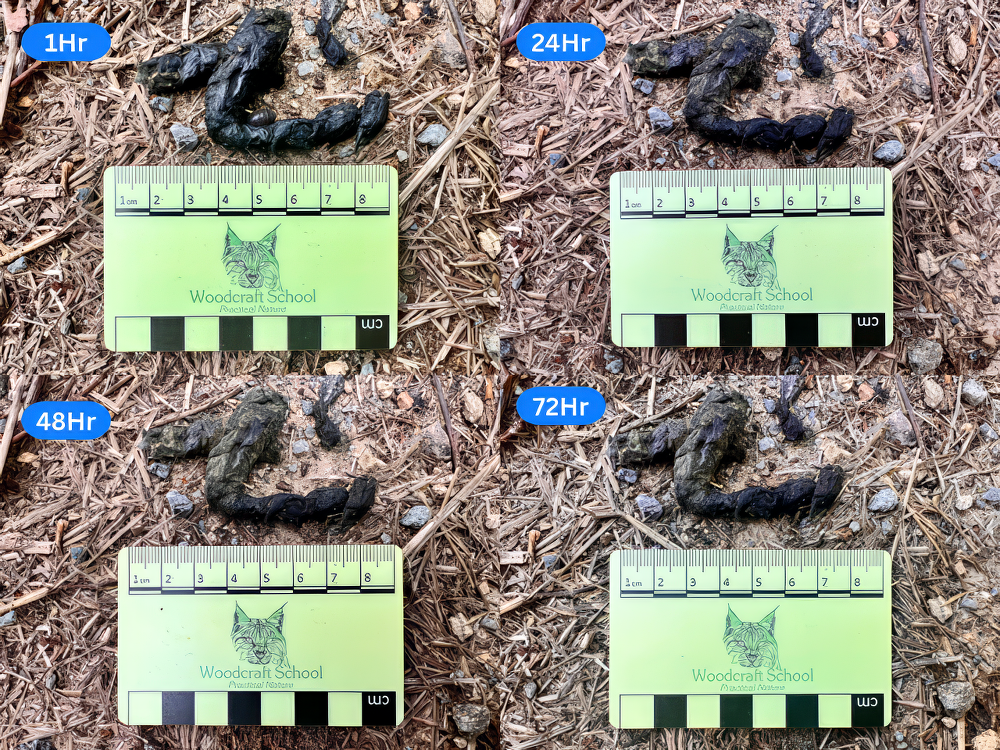

Cameras and den‐box checks in Scotland & N. Ireland revealed:

Spring caches (e.g., 21 May 2015: 44 birds + 8 small mammals + 1 frog = 53 items) reflect surplus juvenile prey during peak vulnerability

Winter caches are minimal (1–2 items), likely opportunistic short‐term stores under deep snow.

6.2. Seasonal Variation

Spring: Large multi‐item caches assist during high‐demand periods (reproduction, territory defence).

Autumn: Caching of fruits is rare or undocumented—martens rely on immediate consumption of berries.

Winter: Short‐term caching of small bird prey provides rapid access near den sites when live prey is scarce and snow‐travel costly.

In July and August Plums form a significant proportion of the diet of our local Pine Martens. Here 2 of them were filmed under one of our plum trees eating windfallen fruit. We also recorded footage of them in the trees picking the fruit directly from the branches.

7. Discussion & Conclusions

Energetic Optimization: Martens select high‐density prey (juvenile rodents, birds) when movement and handling costs are elevated (spring, winter), and exploit spatially concentrated low‐density resources (berries, insects) in summer–autumn.

Caching Strategy: Predominantly a short‐term behaviour in spring—storing abundant juvenile prey near dens to buffer peaks in energy demand. Minimal long‐term caching suggests reliance on seasonal prey phenology rather than extended hoarding.

Movement & Foraging Costs: Foraging distances inversely relate to prey profitability; caching further minimizes revisit costs during high‐demand periods.

Ecosystem Implications: These flexible foraging and caching tactics underscore the pine marten’s role as both predator and seed disperser, linking trophic and plant‐community dynamics in boreal forests.

References

Gilg, O., Sittler, B., & Berteaux, D. (2003). Winter movement cost in Martes spp. Oecologia, 135(2), 286–292.

Helldin, J. O. (2000). Seasonal diet of the pine marten in the southern boreal zone of Sweden. Acta Theriologica, 45(4), 395–403.

Jędrzejewski, W., Jędrzejewska, B., & Zalewski, A. (1993). Foraging by pine marten in Białowieża Forest, Poland. Acta Theriologica, 38(3–4), 405–426.

Martin, J. L., et al. (2020). Daily prey biomass requirements in Martes americana. Ecological Monographs, 90(4), e01462.

Muñoz‐Garcia, A., & Williams, J. B. (2005). Energetics of apples and fruits for small carnivores. Ecology, 86(9), 2450–2465.

Pulliainen, E., & Ollimäki, E. (1996). Food of the pine marten in Finland. Annales Zoologici Fennici, 33, 111–118.

Strickland, M. A., & Douglas, C. W. (1987). Marten movement. In Wild Furbearer Management and Conservation in North America (pp. 531–546). Ontario Trappers Association.

Twining, J., Birks, J., Martin, J., & Tosh, D. (2017). Food caching as observed through use of den boxes by European pine martens (Martes martes). Mammal Communications.

Zalewski, A., & Jędrzejewska, B. (2002). Food selection and movement in a Polish primeval forest. Mammalia, 66(4), 511–522.

Pine Marten FAQ

Are pine martens native to the UK?

Yes. Pine martens (Martes martes) are native mustelids. Once widespread across Britain, they were driven to near extinction but are now recovering thanks to legal protection and reintroduction projects.

Are pine martens rare in the UK?

They’re still scarce in England and Wales, but populations are growing. Scotland remains their stronghold, with expanding ranges in Wales, Shropshire, Cumbria, and the Forest of Dean.

Where do pine martens live?

They favour woodlands — especially native forests with plenty of cover, tree cavities, and old buildings for denning. They also travel along hedgerows, river valleys, and rocky ground.

What do pine martens eat?

They’re opportunistic feeders. Small mammals, birds, insects, carrion, and fruit all feature in their diet. In autumn, berries and nuts are especially important.

Are pine martens dangerous?

Not to people. They’re shy and rarely seen. The main issues occur when they raid unsecured poultry pens, but otherwise they avoid human contact.

How big is a pine marten?

About the size of a small cat. Adults measure 40–55 cm long with a 20–30 cm bushy tail. They weigh 1–2 kg and are easily recognised by their creamy-yellow throat patch or “bib.”

Why are pine martens important?

They help keep ecosystems balanced. Notably, they suppress invasive grey squirrels, giving red squirrels a better chance to thrive. They also regulate rodent populations in woodland.

How can you see pine martens in the UK?

Your best chance is in the Scottish Highlands at dawn or dusk. In England and Wales, sightings are possible in the Forest of Dean, mid-Wales, and parts of northern England where reintroductions are underway.

How do you photograph pine martens?

Use trail cameras first to confirm activity. For in-person photography, hides and long telephoto lenses are essential. Work at dawn or dusk, stay quiet, and never bait or disturb dens.